Home______Enlightenment Gene?

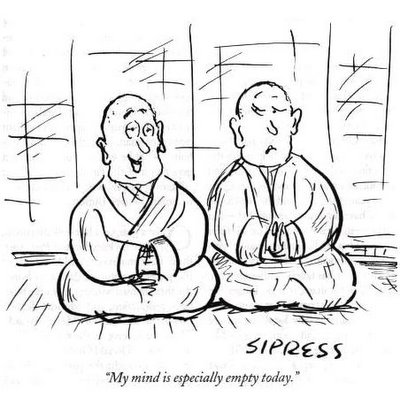

As a meme, the culture for enlightenment is perpetuated through generations. As a gene, the biological capacity for it does not fare as well. People take to the idea of becoming enlightened but those who experience it are rare. This is because a gene for it does not contribute to evolutionary survival value.